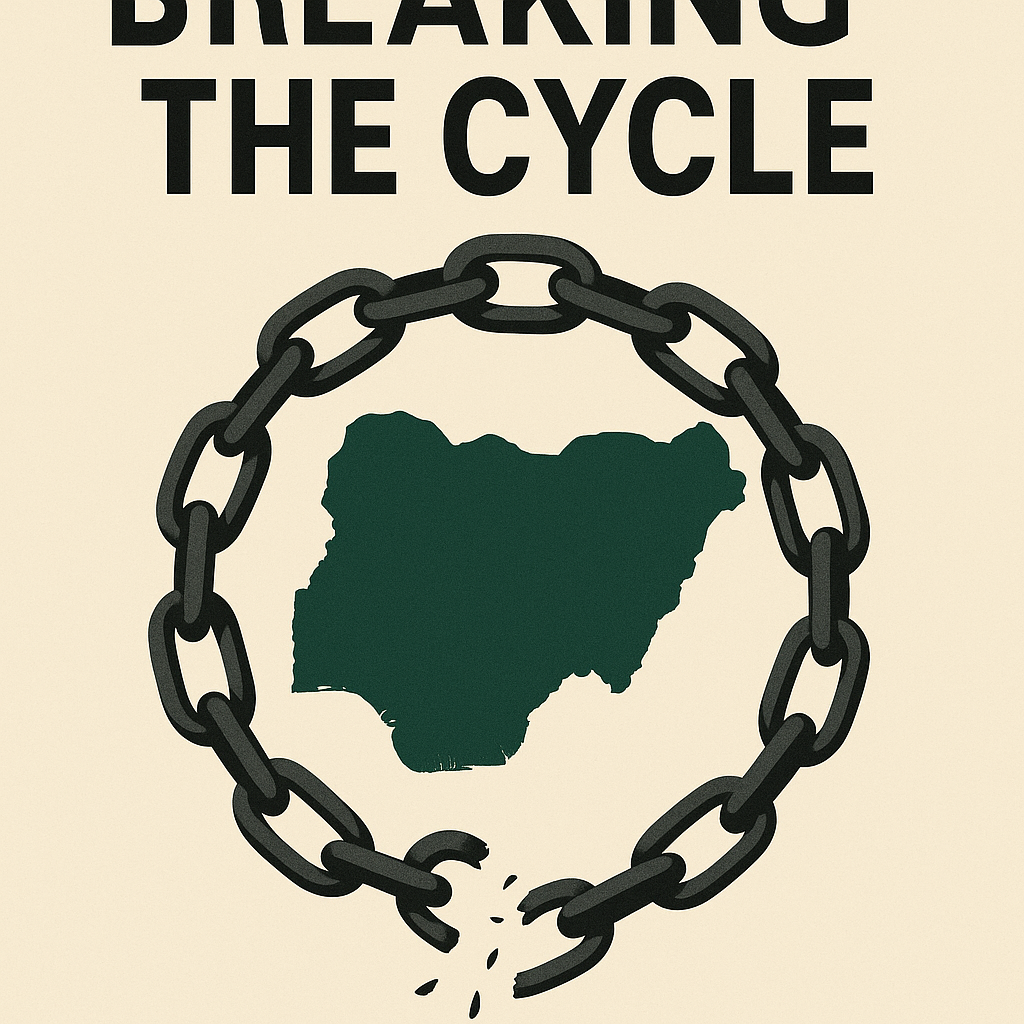

Breaking the Cycle

In the first two parts of this series, we defined political vandalism as the reckless destruction of Nigeria’s institutions, values, and resources, and we examined its many faces — economic, institutional, and cultural. It has left Nigeria poorer despite wealth, weaker despite potential, and more divided despite common destiny.

But the real question is this: how can Nigeria break the cycle of political vandalism?

The first step is to acknowledge that political vandalism thrives on short-term politics. Leaders think in four-year election cycles rather than in generational terms. Every administration wants to stamp its name on new projects while abandoning old ones. To break the cycle, Nigeria must institutionalize policy continuity. National development plans should be shielded from partisan politics so that roads, industries, and reforms do not die with a change of government.

Second, Nigeria needs to rebuild resilient institutions. Strong institutions are the antidote to political vandalism. A civil service insulated from politics, a judiciary that dispenses justice without fear or favour, and universities that produce knowledge rather than endless strikes — these are the backbones of a functioning state. Countries that escaped poverty did so not just through resources, but through institutions that outlived leaders.

Third, the political culture must change. Political vandalism feeds on patronage and dishonesty, but it can be starved by accountability and meritocracy. Citizens must demand more from leaders, not just in words but in action: voting out those who plunder, challenging corruption in courts, and refusing to normalize theft as cleverness. A society that rewards integrity will slowly choke off vandalism at its roots.

Fourth, Nigeria must invest in citizen education and civic engagement. Political vandalism survives when citizens are either ignorant or indifferent. If young people are raised to see politics as service rather than a shortcut to wealth, the future will look different. This is where schools, civil society, and even religious institutions must play a role in reorienting values.

Finally, Nigeria must embrace a long-term vision of nationhood. Countries like Singapore, South Korea, and even post-war Germany rose because they had national goals bigger than any leader or political party. Nigeria, too, must discover a unifying mission — a vision that transcends tribes, religions, and elections. Without it, vandalism will continue because there is nothing sacred to protect.

The cycle can be broken. But it requires courage, not just from leaders, but from citizens. For too long, Nigerians have lived in a house where each tenant vandalizes the walls, the roof, and the floor, hoping to enjoy the space before moving on. The result is a collapsing structure. Breaking the cycle means treating Nigeria as a permanent home — one worth repairing, protecting, and passing on.

In the end, the greatest tragedy of political vandalism is not the money lost, the projects abandoned, or the institutions weakened. It is the theft of hope — the repeated disappointment of a people who know they deserve better. To break the cycle is to restore hope, rebuild trust, and reclaim the possibility of greatness.

Political vandalism may be Nigeria’s original sin, but it does not have to be its destiny.