A groundbreaking discovery is reshaping our understanding of human history. Scientists reexamining a fossilized child’s skull from Skhul Cave in Israel believe it may represent the earliest known evidence of interbreeding between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals—dating back nearly 140,000 years ago.

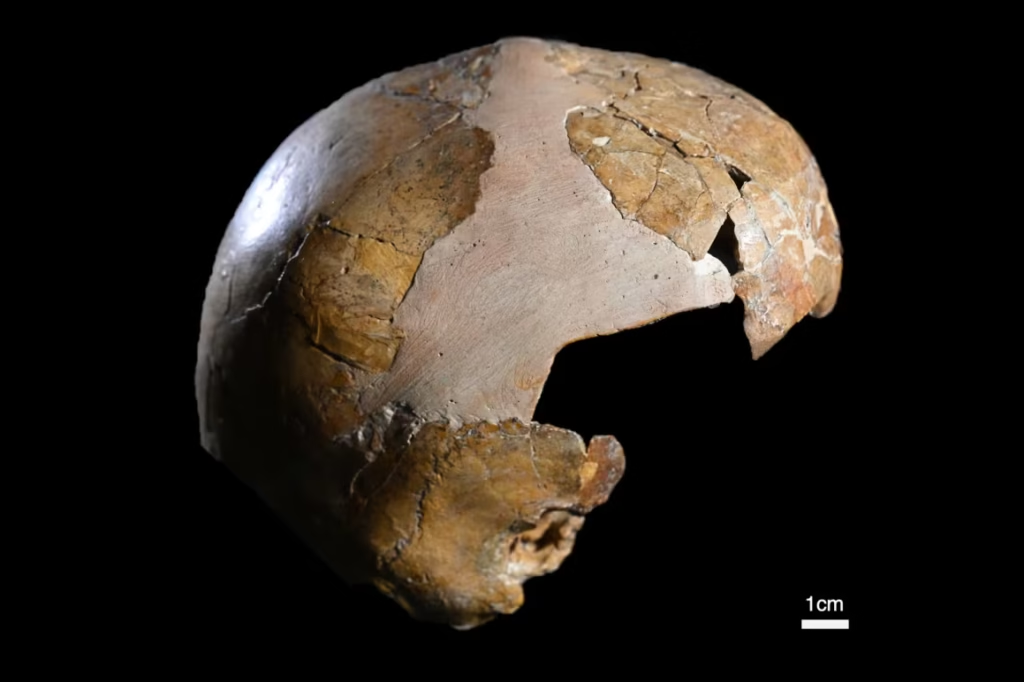

The remains, first unearthed in 1931, belonged to a five-year-old child. Using modern micro-CT scanning and 3D modeling, researchers found a striking blend of features: a rounded braincase typical of early modern humans, alongside Neanderthal-like traits in the jaw and inner ear. This mix of anatomical characteristics suggests the child may have been of hybrid ancestry.

Until now, genetic evidence pointed to interbreeding events occurring around 50,000 to 60,000 years ago, after Homo sapiens left Africa. If confirmed, this fossil would push the timeline back by almost 100,000 years, showing that our species may have interacted with Neanderthals much earlier, particularly in the Levant—a key crossroads between Africa, Europe, and Asia.

The discovery carries profound implications. It challenges long-held views of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals as isolated groups, instead suggesting centuries of coexistence, contact, and even cultural exchange. Far from a story of replacement, human evolution may have been a long, complex process of blending.

Not all experts are convinced. Some caution that physical traits can be misleading, and only DNA analysis can definitively confirm hybrid ancestry. Still, the find adds a powerful new piece to the puzzle of our shared past.

As researchers continue to apply advanced technology to old discoveries, the story of human origins is being rewritten. This child’s skull serves as a reminder that the lines between species were blurrier than we once imagined—and that the roots of humanity are far more interconnected than we thought.